We Care About Your Privacy

By clicking “Accept all”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts. View our Privacy Policy.

Beckmann (2009) defines the term ‘cross-curricular teaching’ as ‘instruction within a field in which subject boundaries are crossed and other subjects are integrated into the teaching (how and for whatever purpose or objective)’.

Inadvertently, many teachers apply cross-curricular teaching in their classrooms as part of their practice. However, if we put our knowledge, intent and planning into it, cross-curricular teaching becomes a wonderful and very powerful tool in the classroom. Due to the fact that it promotes a holistic understanding of the subjects taught, fosters crucial critical thinking skills and prepares learners for success beyond the classroom, it provides a much-desired dynamic environment and engaging approach in the classroom.

According to Cummins (2000), “cross-curricular teaching enhances language acquisition by providing meaningful contexts for language use and promoting the integration of language and content knowledge.” This is extremely relevant and important for those learning EAL (English as an Additional Language) in English-medium schools. EAL learners have a hard job to learn English (and to learn in and through English). Cross-curricular teaching allows them to integrate content and skills from multiple subject areas into one holistic educational experience. That way, EAL learners have the opportunity to see the connections between different subjects in the curriculum and the everyday language they need to be able to socialise in and out of school. In addition, they can develop a deeper understanding of certain concepts. Lucas and Villegas (2013) agree that “cross-curricular approaches support EAL learners in making connections between different subject areas, fostering holistic understanding and critical thinking skills.”

In their research, Calderon and Sanchez (2011) support this by saying that “integrating language instruction with content learning helps EAL students develop a deeper understanding of academic concepts while simultaneously advancing their language proficiency.”

The examples listed below demonstrate how cross-curricular teaching can enrich learners’ experiences by integrating content, skills and knowledge from different subjects in meaningful and engaging ways. Genesee, Lindhold-Leary, Saunders and Christian highlight that “collaborative learning opportunities embedded in cross-curricular instruction provide EAL learners with valuable language practice and promote social interaction, leading to enhanced language development.”

Incorporating some cross-curricular strategies when teaching EAL learners can be highly beneficial, as it helps them not only improve their English language skills but also understand other subjects better. According to Short and Fitzsimmons (2007), “by integrating language learning with content instruction, cross-curricular teaching creates authentic language use situations that support EAL students in developing both academic language skills and content knowledge.”

By integrating cross-curricular content into English language teaching and learning, EAL learners can develop language skills whilst simultaneously gaining knowledge in other curricular subjects. This inevitably leads to a more comprehensive and engaging learning experience as well as promoting academic success.

Here is an example of how you can plan for both content and language:

Medium-Term Cross-Curricular Planner for Learning Content and Language

|

Subject: History |

Content learning objective |

English language learning objective |

Cross-curricular links |

Notes |

|||||

|

Term 1 |

Identify key contributions of ancient civilisations to areas such as architecture and literature. |

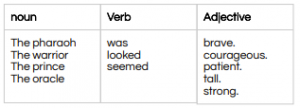

Past Simple tense (regular and irregular forms) – e.g. The oracle predicted a flood. The pharaoh built a pyramid. Use of ‘used to’ – e.g. This country used to be a republic. Passive Voice – e.g. The country was ruled by a dynasty. Descriptive adjectives – e.g. The warrior was brave and courageous. |

Geography – link to climate, materials, topography, cultural factors English – Exploring ancient texts, adapted poems or religious texts and doing comparative analysis using translations; link to values, culture and history; comparing characters; etymology and link to Latin and Ancient Greek |

||||||

Lesson plan for EAL learners with a lower level of proficiency in English

Topic – Ancient Civilisations

Content learning objective: To describe basic key features typical for ancient civilizations

English language learning objective: To apply key vocabulary in own sentences using regular verbs in Past Simple tense and adjectives for descriptions.

Key vocabulary

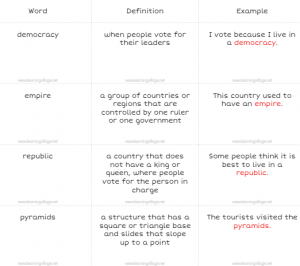

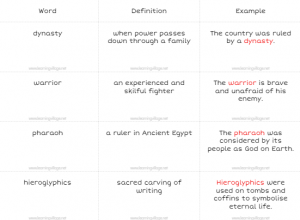

pharaoh pyramids hieroglyphics democracy acropolis republic empire dynasty aqueduct warrior oracle

Activities

Instructions:

Instructions:

Learners write their own examples using the key vocabulary and a substitution table.

For EAL learners who are at a higher English language proficiency level, this substitution table might be used:

Extension: Learners research the writing system of an ancient civilization of their choice, e.g. Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome, the Maya, the Inca. What links can they find between words from that civilization and English?

For example, Latin prefixes in English, such as ‘pre-, re-, post-’.

References

Beckmann, A. (2009). A Conceptual Framework for Cross-Curricular Teaching. The Mathematics Enthusiast: Vol. 6: No. 4, Article 1.

Calderón, M., Slavin, R., & Sánchez, M. (2011). Effective Instruction for English Learners.

Cummins, J. (2000). Language, Power, and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire.

Genesee, F., Lindholm-Leary, K., Saunders, W. M., & Christian, D. (2006). Educating English Language Learners: A Synthesis of Research Evidence.

Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2013). A Framework for Preparing Linguistically Responsive Teachers.

Short, D. J., & Fitzsimmons, S. (2007). Double the Work: Challenges and Solutions to Acquiring Language and Academic Literacy for Adolescent English Language Learners

Many researchers agree that note-taking is an important skill, as it facilitates learning from text (Kobayashi 2006, Rahmani and Sadeghi 2011, Wilson 1999). Siegel (2015) iterates that note-taking benefits second learners, as it provides them with an ‘external record’ which they can use for future tasks and review. Furthermore, Dyer, Riley and Yekovich’s 1997 study confirmed the effectiveness of note-taking in enhancing reading skills.

Coreen Sears gives us an insight into her thoughts...

If you have the opportunity to use a bilingual support partner to help families who have learners working from home, it may be useful to prepare a list of questions for this staff member to ask. Bilingual support is extremely useful when making contact with parents who speak little or no English.